Cybercriminals use of social engineering— the psychological manipulation of people into performing actions or divulging sensitive information—as the most common way to steal information, money or even assume others’ identities. Social engineering is at the heart of all types of phishing attacks—such as those conducted via email, SMS/text messaging, and phone calls. Current technology makes these sorts of attacks easy and very low risk for the attacker, so it is important that we are all aware of and vigilant for these types of attacks and techniques.

Social Engineering Techniques

- Phishing: The process of attempting to acquire sensitive information (such as passwords, bank account information, and credit card details) via email by posing as a trustworthy entity. Emails claiming to be from University senior management (President, Dean, Vice President), IT personnel, popular social web sites, banks, and credit card provides are commonly used to deceive the email recipient(s).

- Often, when someone falls victim to a phishing attack and provides their account credentials, the attacker then utilizes their email account to send additional phishing attacks to that individual’s contacts, attempting to get access to additional accounts and sensitive information.

- Spear Phishing: A small, focused, targeted attack via email on a particular person or organization. The spear phishing attack is done after research on the target and has a specific personalized component designed to make the target do something against their own interest.

- Smishing: Phishing attacks via mobile device text messaging application attempting to trick users into supplying information or clicking on links in a text message. Often the text message will contain an URL or phone number. The phone number often has an automated voice response system. And again, just like phishing, the smishing message usually asks for your immediate attention. Flaws in how caller ID and phone number verification work make this an increasingly popular attack that is hard to stop.

- Pharming: Pharming is where an attacker installs malicious code on a computer or server. This code then redirects any clicks you make on a website to another fraudulent website, without your consent or knowledge.

- Vishing: Phishing conducted via phone call. These calls often claim to be other entities, such as government agencies, software vendors, or organizations offering to help with benefits or credit card rates. Attackers will often appear to be calling from your own area code or a local number close to yours. As with smishing, flaws in how caller ID and phone number verification work make this a dangerous attack vector.

How to Identify Social Engineering Red Flags

While the University has several controls to reduce the impacts of these attacks, attacks can still happen due to human error. Therefore, to best mitigate or avoid these attacks, every member of the University community must be vigilant and diligent in identifying social engineering red flags:

- Unexpected and/or vague requests: Ignore any unexpected or vague requests, such as unclear SharePoint or OneDrive file-sharing requests or to hastily circumvent policy or procedure.

- Misspellings and/or poor grammar: Often you will find misspellings and/or poor grammar within social engineering attacks, especially if the message appears to be from someone you know and the language utilized is much different than to what you are accustomed.

- Scare tactics: These attacks depend on scaring you, such as with a lawsuit, that your computer is full of viruses, your account may be locked, suspended, or deleted, that your personal information may be divulged, or that you might miss out on a deal that is too good to be true. Do not react to scare tactics!

- Urgency: Review the words or phrases that indicate a deadline or a need to take quick action (i.e. individual needs to get into the building because of a late meeting). Some of these words or phrases could include "final notice," "urgent," "action required," "your account will be deleted,” or “your account will be locked.”

- Misleading hyperlinks: Always review web addresses (URLs) in hyperlinks. Hover over hyperlinks and ensure the URL relates to the location you are expecting to go. Malicious websites may look identical to a legitimate site, but the URL may use a variation in spelling or a different domain (e.g., .com versus .net). If the website looks different than when you last visited, be suspicious and do not enter any personal or financial information unless you can verify that the site is secure.

- Deceiving Sender email addresses: Malicious individuals use misspelled email addresses, obfuscated email addresses (e.g. testperson.neomed.edu@gmail.com instead of testperson@neomed.edu), spoofed email addresses (i.e. appears to be a an email from a neomed.edu account however does not actually exist), or compromised email accounts (i.e. someone who had their credentials compromised and now a malicious user is attempting to phish others) to mislead the recipient.

- Browser warnings: Be aware of any warnings that your web browser may display (i.e. warning screens, dangerous labels next to the web address.)

Phishing Example and Red Flags

Here is an example of a real phishing attack the University received and the red flags associated with it:

- Red Flag (1): Scare tactics – The email subject indicates that the individual’s email account will be suspended, encouraging the individual to open the email to review the content.

- Red Flag (2): Deceiving Sender email addresses – It appears that this is coming from a legitimate neomed.edu email address, however this attempt is making it appear real (spoofing). Additionally, University IT emails do not come from this address.

- Red Flag (3): Misspellings and/or poor grammar – This portion of the message includes poor grammar, such as missing words and incorrect verb/subject agreement.

- Red Flag (4): Misleading hyperlinks – Upon hovering over the hyperlink, the web address listed is taking the user to “storage.googleapis.com” (expected to go to a Microsoft page) and includes a “redirect” command. This is an attempt to redirect someone to a malicious site.

How Can I Verify Something is a Social Engineering Attempt?

If you are ever unsure whether if a request or message is legitimate, contact the NEOMED Help Desk. You can also take steps when you identify social engineering red flags determine if the request is legitimate or not:

- Verify any suspicious requests by contacting the individual/entity independently. Legitimate companies and organizations will give you a real business address and a way for you to contact them back, which you can independently verify on a company website, support line, etc. Do not trust people who contact you unexpectedly claiming to represent the University. If you receive an email or phone call requesting you call them and you suspect it might be a fraudulent request, look up the organization’s customer service number and call that number rather than the number provided in the solicitation email, phone call, or text message. If you are unsure whether an email request is legitimate, contact the organization using information provided on an account statement or other source, not the information provided in the potentially fraudulent email.

- The President of the University emails you unexpectedly to purchase gift cards. Instead of doing so, you should notify the NEOMED Help Desk and call the President’s Office to verify its legitimacy.

- You receive a call from what you believe to be your credit card company stating that your account has odd activity on it and you need to provide your credit card details over the phone to verify they are talking to the correct person. Instead of doing so, you should request their name and phone number and indicate you will call them back. After hanging up, you should call the number printed on the back of your credit card and speak to a different representative confirming that odd activity is legitimate.

- Review an email header’s sender email address: An email header is a log of an email’s technical details that both the sender and recipient can see, including any email addresses that are involved in the conversation, the servers the email passed through while being sent, and more. By reviewing email headers, you can compare the email address presented in your email to the sender address in the email header. If they do not match and you see an irregular or odd email address within the email header, it is likely fraudulent.

See this brief Microsoft how-to article: View Email Headers in Outlook

When in Doubt, Report it Out!

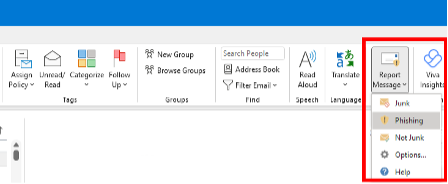

If you think you may have encountered a phishing email, the quickest way to report it is to use the “Report Message” button in Outlook. Using this built-in tool will train your inbox to better recognize junk and phishing emails. If you suspect a message to be phishing, under the “Home” or “Message” tabs in Outlook, you can click the “Report Message” button and select “Phishing” from the drop-down menu.

Alternatively, you can forward a phishing email to itsecurity@neomed.edu.

Regardless of the method, the sooner you report a suspected phishing email, the sooner NEOMED IT Security personnel can act on it. There are no consequences to reporting a suspicious email – when in doubt, report it out! And whatever you do, do not click on any links, reply to the email or send it to anyone else.

What Should I Do if I am a Victim of Social Engineering/Phishing?

- Watch for any unauthorized charges to your account(s). If you believe your personal financial accounts may be compromised, contact your financial institution immediately to get guidance on freezing or closing the account(s). Additionally, you can flag your credit reports by contacting the fraud departments of any one of the three major credit bureaus: Equifax (800.685.1111); TransUnion (888.909.8872); or Experian (888.397.3742).

- Consider reporting personal attacks to your local police department and filing a report with the Federal Trade Commission or the Internet Crime Complaint Center. Make sure you keep a copy of the police report in a safe place.

University Training and Associated Policies

Other Resources

Below are some short videos (2-4 minutes) and articles that provide more information and tips on social engineering: